Loose Pucks: Curse of the Blue Shirts

Posted: January 29, 2013 Filed under: Loose Pucks (Miscellaneous) Comments Off on Loose Pucks: Curse of the Blue ShirtsJanuary 29, 2013

As discussed previously, new Sharks pickup Scott Gomez is attempting to reverse a steep career decline. The former star’s career has plummeted from lofty heights — taking home the Calder Trophy as rookie of the year and winning two Stanley Cups with the Devils — to stunning lows — a humiliating contract buyout in Montreal and a spot on the fourth line in San Jose.

Gomez suffered a sharp decline in production after his first year in Montreal. In 2009-2010, after the Canadiens acquired Gomez and the rest of his $51.5 million seven-year contract from the Rangers, he scored 59 points in 78 games, or 0.756 points per game. In the following two seasons, he produced only three more points while playing 40 more games, for a point-per-game average of 0.525. That’s more than a 30% drop in scoring.

No one seems able to explain the sudden and drastic loss of scoring ability, least of all Gomez himself. During the dark days of his more than year-long stretch without scoring a goal, The (Montreal) Gazette could only ask plaintively, “Will Scott Gomez ever score again?” Gomez simply expressed disbelief: “This whole thing is surreal to me now. I can’t help but think: ‘Are you kidding me?'”

But Gomez may not be directly responsible for the spectacular collapse of his hockey career. Perhaps he simply succumbed to the malady that has claimed many stronger victims before him: the Rangers curse.

It was the New York Rangers who originally signed Gomez to the bloated contract that Montreal just unloaded. Before the Rangers came calling, Gomez was doing just fine in New Jersey. Then the spendthrift Rangers snapped up their Tristate neighbors’ rising star, showered him with cash, and ushered in the inevitable demise of his hockey career.

The Rangers have a history of spending freely (and conspicuously) to buy other teams’ talent. Why nurture home-grown talent when you can just buy players someone else nurtured for you? Like any rich New Yorker, the Rangers aren’t about to take the subway to success when they have plenty of cash to pay for a cab.

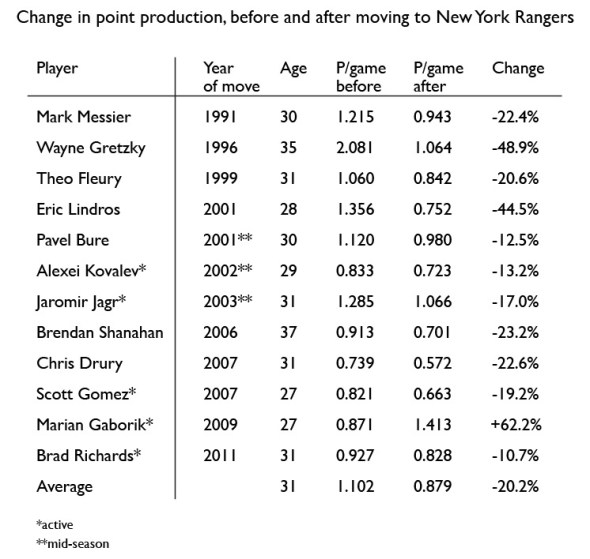

The trouble is, most of their blockbuster acquisitions broke down after a few miles. Moving to Manhattan, for NHL players, can spell doom for even the most promising career. Consider these statistics for the following 12 high-profile Ranger acquisitions during the 1990s and 2000s:

The wrong move

Mark Messier led the Rangers to a Stanley Cup, and he still couldn’t escape the Rangers curse; his scoring dropped 22%. Wayne Gretzky is Wayne Gretzky, and he couldn’t escape it either: his points per game decreased almost by half.

Even Alexei Kovalev couldn’t escape the Rangers curse, and he started with the Rangers. But then he went to Pittsburgh for five seasons, where he recorded a career-high 95 points in 2000-2001. After enjoying success outside New York City, Kovalev was just asking for trouble when he moved back to the Rangers during the 2002-2003 season. His point production dropped by 13% from his previous average (including his original stint with the Rangers). Leaving another NHL team and moving to Madison Square Garden is how players catch the Rangers curse, and previous exposure does not provide immunity.

One player does seem to have overcome the odds and beaten the curse: Marian Gaborik has so far achieved an increase in points per game since coming to the Rangers, though he will still need to monitor the remaining years of his career for symptoms. Maybe he has a genetic anomaly that reduces his susceptibility. Even the Black Death spared a lucky few.

Overall, however, the data clearly establishes substantial loss in scoring following a move to the Rangers. Of course, other factors could contribute to the post-Rangers decline in scoring — lack of chemistry with new teammates, perhaps; difficulty coping with the pressure of a gaudy contract and heavy expectations; or simply the passage of time as players enter the later stages of their careers. To determine the true effect of the Rangers curse independent of general adjustments, normal career decline, and other secondary factors, a control group is needed. Fortunately, history provides the perfect case study, the superstar player the Rangers went after but didn’t get: Joe Sakic.

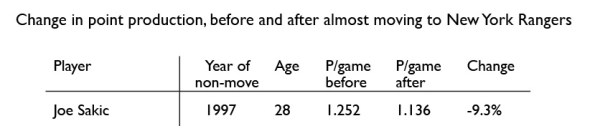

In the summer of 1997 the Rangers signed Sakic, then a Group 2 free agent, to an offer sheet. Had the Avalanche not matched the offer, Sakic would have begun his Rangers career the following season. Here are his numbers:

Dodged a bullet

Like the sufferers of the Rangers curse, Sakic produced fewer points in the second segment of his career — that is, during the seasons following his near-move to the Rangers. But Sakic’s scoring decreased by only 9.3%, while scoring by the players who actually did move to the Rangers dropped by 20.2%, more than twice as much. Sakic was younger at the time of his non-move than the Rangers group as a whole when they did move, but Eric Lindros is the only Ranger of comparable age whose career, like Sakic’s, has already ended — and Lindros suffered a particularly severe case of the curse with an appalling 44.5% drop in scoring.

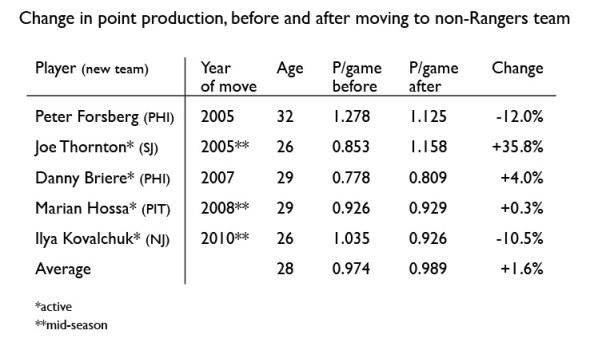

Sakic’s unique status as an almost-Ranger provides a helpful comparison, but he’s still only one player — too small a sample size to be convincing alone. For a second control group, consider the following six high-profile acquisitions by teams other than the Rangers:

Good hygiene

On average, prominent players who moved to teams other than the Rangers actually increased their scoring slightly after the move. The difference between the non-Ranger group’s 1.6% increase in scoring and the Ranger group’s 20.2% decrease is almost 22 percentage points.

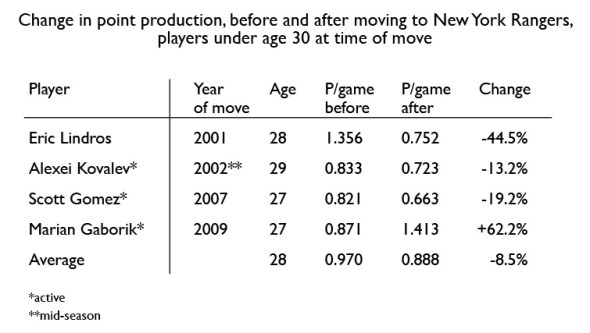

In fairness, these players were three years younger than the Rangers group, as a whole, when they changed teams. (Age at the time of the move is based on opening day of the new season for offseason acquisitions or the date of the trade for mid-season acquisitions.) Just to be sure, look at the Rangers group again, this time limiting it to players under age 30 when they moved:

Young and robust … but not immune

These younger players changed teams at the same age as the control group (28 on average), but their scoring still decreased 8.5% compared to the control group’s 1.6% increase — a 10-percentage-point difference. While this particular comparison is useful for addressing the age factor, it’s important to note that most players in this age group — both Rangers and non-Rangers — are still active in the NHL, so their final career trajectories are yet to be determined.

Taken in totality, however, empirical analysis of the available data leads to only one conclusion.

Yes, the Rangers curse is real. But how bad is it really?

To put the numbers in perspective, it’s helpful to see what a small percentage-point difference can mean in terms of real-life changes. Conveniently, the real world offers a useful model in the stock market, which like a hockey player’s scoring is measured in points.

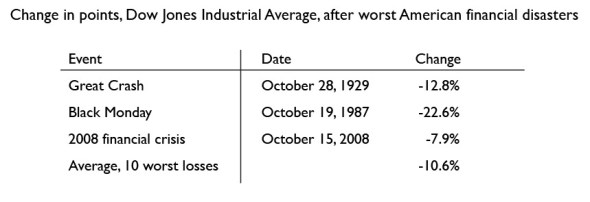

Based on data from The Wall Street Journal, here are three of the worst one-day losses in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, as well as an average of the 10 worst losses all time, in U.S. history:

Free fall

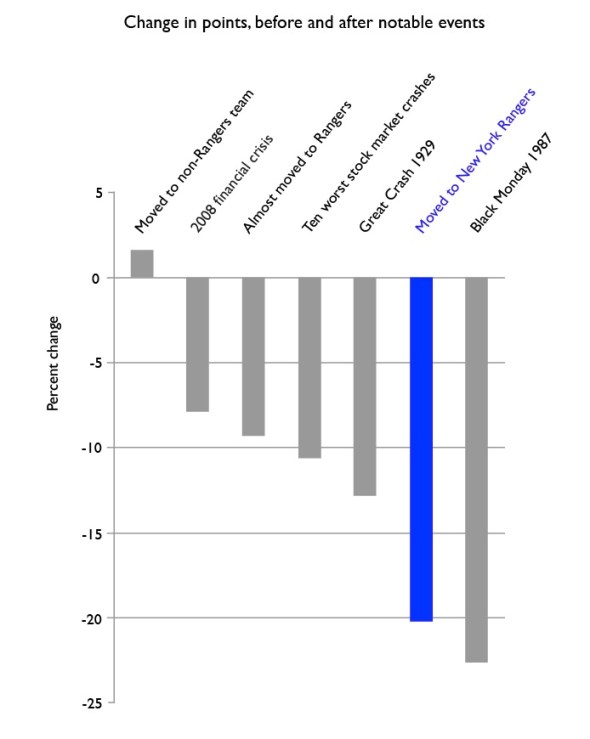

Put it all together and a clear picture emerges, revealing a virulent sickness in the NHL. For the visually oriented, here is the data aggregated in a graph showing the percentage change in points before and after several notable events, including a move to the New York Rangers:

Worst calamities

Distilled into simple terms, the Rangers curse is more destructive than the stock market crash preceding the Great Depression. But the effects of the curse are slightly better than the single worst nosedive in American financial history, Black Monday in 1987. Perhaps new additions to the Rangers can find a measure of comfort in that fact.

Can a cure be found? Funding for research has yet to present itself, despite all of the disease’s victims being celebrities. The prospects for treatment seem dim.

Rick Nash, take your vitamins.

Loose Pucks: The Great Gomez

Posted: January 27, 2013 Filed under: Loose Pucks (Miscellaneous) Comments Off on Loose Pucks: The Great GomezJanuary 27, 2013

Every NHL team begins the regular season in pursuit of the same elusive (and for some, highly improbable) goal: winning the Stanley Cup. This season, the always ambitious San Jose Sharks have undertaken what may be an even more daunting challenge: resuscitating the career of Scott Gomez.

Gomez’s last two seasons as a Montreal Canadien were, as the Anchorage Daily News diplomatically puts it, “unproductive”: 9 goals in 118 games, including an infamous 368-day drought1 between goals. Despite general manager Marc Bergevin’s previous statement to the contrary — “I’m not buying him out,” Bergevin told LNH.com last July — Montreal placed Gomez on waivers and bought out his contract on January 17. How much is it worth to Montreal to be rid of Scott Gomez? The Canadiens will pay $9.2 million to Gomez over the next three years to not have his services.

Gomez’s career hit its lowest point (he hopes) on November 7, 2012, during the NHL lockout, when he signed a contract with the Alaska Aces of the ECHL. The ECHL is a “developmental league for the American Hockey and the National Hockey League” — in other words, two tiers below the NHL, sort of like Double-A baseball. Double-A is where Michael Jordan played baseball, and he was coming from a sport where the ball is a totally different size and color. Scott Gomez went to the second-tier minors in his own sport, where pucks come in only one size and color.

Here are some of the most frequently asked questions on the ECHL website:

- What do the letters ECHL stand for? (Answer: East Coast Hockey League.)

- What is the minimum salary for an ECHL player? (Answer: $425 per week.)

- How can I try out for an ECHL team? (Answer: After “selecting a team logo on the top of the site,” simply “contact the general manager or coach.”)

The Alaska Aces commended Gomez as “the most decorated hockey player from Alaska”; the Anchorage Daily News echoes that he’s “the most accomplished hockey player from Alaska.” He may even be able to see the KHL from his parents’ house in Anchorage. In happier times, Gomez brought the Stanley Cup to his hometown of Anchorage and went to Hollywood for a cameo role in the daytime soap opera One Life to Live.

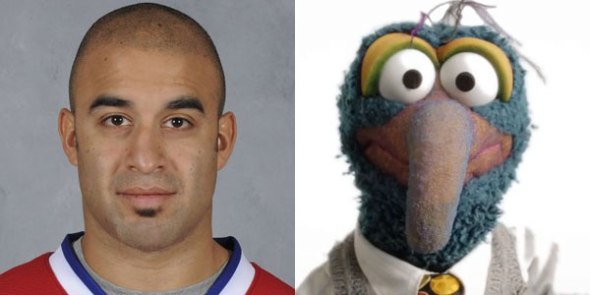

But by now, like the down-on-his-luck Gonzo the Great in Disney’s 2011 movie The Muppets, Gomez must know that his “career is down the drain.”

Perhaps he can find inspiration in Gonzo, who after a stint in the plumbing business managed to revive his trademark “stage act, which includes shooting himself from a cannon, balancing a piano on his nose, or eating radial tires to classical music.” Compared to those tricks, putting a puck in a net should be easy.

Alaska’s best and the Muppets’ … whatever

Scott Gomez hopes so. Now that the Sharks have taken him on, he’s eager to prove himself. “It just feels like ages since I’ve played in an NHL game,” he told the Daily News, adding helpfully, “I know I can play.”

Gomez isn’t satisfied merely to play again in the NHL, though; he wants to go all the way. “I’m addicted to winning,” he told The (Montreal) Gazette on the day he signed with the Sharks. (One can only wonder how he’s survived the withdrawal.) “You play to have a shot at a Stanley Cup, especially if you’ve won one. I’m not ready to give that up.”

The revitalized Gomez apparently believes his new team can help him get his Stanley Cup fix. Others agree that the new contract amounts to a rescue. Perhaps inspired by San Jose’s marine mascot, several observers have employed a nautical metaphor to describe the Gomez signing. From The Vancouver Sun: “the Sharks have thrown him a lifeline.” From CBC Sports: “Scott Gomez resurfaces with Sharks.” And the headline in The Gazette: “Gomez grasping at Sharks lifeline.”

But are the Sharks really the right team to rescue Scott Gomez from drowning in hockey ineptitude? The Sharks themselves have been lost at sea for years, and every time they saw land on the horizon it turned out to be a mirage: regular-season wins masquerading as signs of imminent playoff success. San Jose has earned a top-four seed in the playoffs every year since the 2006-2007 season, with a combined 295-141-56 regular-season record and a 0.600 winning percentage. According to the analysts at NHL.com, “It’s not often a conversation about the top teams in the Western Conference each season doesn’t include the San Jose Sharks,” and they have been “a serious Stanley Cup contender” ever since acquiring Joe Thornton in 2005.

Yet year after year the Sharks have failed to contend for the Cup in the Finals. Twice they reached the conference finals, but they won only one game in the two series combined; in 2010 they were swept by the eventual Stanley Cup champions, the Blackhawks, and in 2011 they managed only one win against their fellow Western Conference chokers, Roberto Luongo’s Canucks. In three of the remaining four seasons in which the Sharks entered the playoffs as a top seed, they exited in first-round defeats to their lower-seeded opponents. Since 2007, the Sharks have lost 34 of 61 postseason games for a 0.443 win percentage.

This is the team you want towing you to shore?

For Scott Gomez, it is. He made his Shark Tank debut yesterday in a shutout victory over the Colorado Avalanche. In case you’re wondering, no, he did not score a goal.

Speaks for itself: from the wonderful folks at DidGomezScore.com

Gomez replaced fellow center James Sheppard on the fourth line — small skates to fill for a former top-six forward and two-time All-Star. Sheppard, drafted 9th overall by Minnesota in 2006, totaled 53 points in his first two seasons with the Wild but scored only 6 points in 64 games in 2009-2010. He spent last season in the AHL; in his two games with the Sharks this season, Shepard racked up a total of 14:47 on the ice with 2 shots and 2 minutes in penalties.

Gomez was able to top Sheppard’s numbers with 15:03 of ice time and 3 shots on goal in his first game for San Jose, but he also muffed a golden opportunity to score late in the third period when, as the San Jose Mercury News described it, he got “a look into a wide-open net, only to lose control of the puck.” Maybe the pucks in Double-A are less slippery or not as round.

If Gomez was drowning when San Jose dragged him aboard, the Sharks themselves were treading water at best. Now the player best known for scoring futility and the team best known for playoff disappointment will try to carry each other to the misty, far-off land of champions.

1 Calculation based on goals scored on February 5, 2011, and February 9, 2012, not including the dates each goal was scored.

Loose Pucks: Popcorn, Pretzels, and Pucks

Posted: January 22, 2013 Filed under: Loose Pucks (Miscellaneous) Comments Off on Loose Pucks: Popcorn, Pretzels, and PucksJanuary 22, 2013

With the lockout over and an abbreviated season underway, the NHL has concluded the vexing business of CBA negotiations and briskly moved on to the business of marketing the league.

In its celebratory slogan “Hockey Is Back,” the NHL has adopted the grateful tone of a pet owner whose lost puppy finally showed up on the doorstep after a bewildering absence. Never mind that the NHL owners threw their puppy out in the cold four months ago and locked the door. Fido is home again now and all is forgiven.

The last time owners were reunited with their wayward puppy, they expressed their gratitude with extravagant gestures: miniature Stanley Cup replicas handed out to fans at every home opener and the words “Thank You Fans” painted on the ice in every arena. This time, the owners are more jaded. They’ve been through this routine before.

So the NHL is bypassing any organized league-wide demonstration of appreciation for the fans, instead leaving the task to individual teams who, as the league put it in a lukewarm announcement, are thanking fans for their loyalty “using a variety of methods.”

Some NHL clubs, in keeping with the league’s apathetic response, are marching ahead with business as usual, making only perfunctory mention of the new CBA and redirecting fans’ attention to routine news items such as roster moves, ticket sales, and season previews. Among the teams choosing to move on quickly and forgo conciliatory post-lockout gestures to the fans are the Bruins, Oilers, Devils, Rangers, and Canadiens. Attempts at fan appreciation are noticeably absent from the news headlines on these teams’ websites.

The Rangers focused on bigger news, such as the expansion of the Crown Collection, a Henrik Lundqvist-designed fashion line featuring “a signature fitted jacket, hooded sweatshirt, a new fitted cap style, a knit scarf,” and “select novelty items.” After all, although Lundqvist’s performance on the ice so far is weak — a 4.77 goals-against average and 0.865 save percentage, ranking 34th and 32nd respectively in a league with 30 starting goaltenders — his fashion sense is unbeatable.

Not all NHL teams are taking their fans for granted, however. Some franchises spared no expense in showing goodwill to their fans. Both the Avalanche and Lightning offered fans the chance to buy a hot dog for only one dollar. The Lightning also offered a $2 beer special and hosted “Free Lunch Friday with the Lightning,” serving “hot dogs, Italian sausages, and hamburgers” (vegetarians were out of luck).

The Blues could only swing a buy-one-get-one-free deal for their hot dogs, for which they normally charge $4 each, meaning Blues fans were still paying twice as much as Colorado and Tampa Bay hot dog eaters for their discounted convenience-store fare. The Blues made up for the pricey hot dogs by offering “a FREE 12 oz. Pepsi” (drinkers of Coke, despite being on the winning side of the cola war, were out of luck). And as if hot dogs and soft drinks weren’t enough, lucky Blues fans also received “a coupon good for $10 off a $50 purchase at Famous Footwear.”

The most appreciated fans, though, were those in Pittsburgh and Washington, where fans were treated to a smorgasbord of movie-theater-quality food. The Capitals even added dessert to the menu, providing “[c]omplimentary fountain soda, popcorn, pretzels, hot dogs, nachos and ice cream” at their “special Thank You event” for fans. Penguins fans got no ice cream but were given “a voucher for three free concession items” and could “choose from among hamburgers, hot dogs, chicken sandwiches, nachos, popcorn, pretzels, salads and fountain drinks.”

Although not related to the lockout, the Flyers announced a junk food deal for their fans too. Thanks to “their season-long partnership with Papa John’s,” purveyor of mediocre delivery pizza, fans will receive 50% off their order after any game in which “the Flyers score 3 goals or more and win.” Flyers fans may want to make other dinner plans, however, since Philadelphia is 0-2 with a total of three goals scored so far this season.

With or without pizza and hot dogs, and despite scattered threats of boycotts and other fan retaliation for the lockout, fans are returning to the NHL. The league’s apathetic reception of its fans has been rewarded with sellout crowds and record TV ratings, a fact smugly noted by commissioner Gary Bettman.

For better or worse, the NHL doesn’t need to give its fans cheap food to win back their patronage. A deeper hunger brings them back, one the league can take no credit for: the love of hockey.

Reading the Play: When Captains Abandon Ship

Posted: July 26, 2012 Filed under: Reading the Play (Commentary) Comments Off on Reading the Play: When Captains Abandon ShipJuly 26, 2012

Some major names made headlines in the NHL this week. The big news out of Columbus on Monday?

Blue Jackets GM Scott Howson bubbled over with enthusiasm as he announced the deal: “We are excited to complete this trade today as we believe the acquisitions … have advanced the club and put us in a stronger position to achieve our goal of winning the Stanley Cup.”

To help introduce Columbus fans to the new players who will be leading the charge for the Cup, the Blue Jackets summarized their career highlights to date:

- Two seasons ago Brandon Dubinsky “set career highs” in goals, assists, and points. (This past season, according to official NHL statistics, his scoring fell by 20 points, almost a 40% drop in production.)

- Four years ago Artem Anisimov ranked fifth in scoring in the American Hockey League. Also, his name is “pronounced a-NEE-see-mawv.”

- Last year Tim Erixon ranked second in points among defensemen on the AHL’s Connecticut Whale. No pronunciation guide was provided for his name.

Talent of that caliber doesn’t come for free, of course, so in exchange the Blue Jackets sent Steven Delisle, a conditional third-round pick, and their captain Rick Nash to New York. The considerate Blue Jackets helpfully summarized the career highlights of Nash as well. He “is the Blue Jackets’ all-time leader in”:

- games played (674)

- goals (289)

- assists (258)

- points (547)

- power play goals (83)

- power play points (182)

- game-winning goals (44)

- shorthanded goals (14)

- hat tricks (5)

- shots on goal (2,278)

- multi-goal games (45) and

- multi-point games (136)

Also, this past season “he led the club … in goals (30) for the eighth straight season and points (59) for the fifth straight season … , while setting a career high in games played (82).”

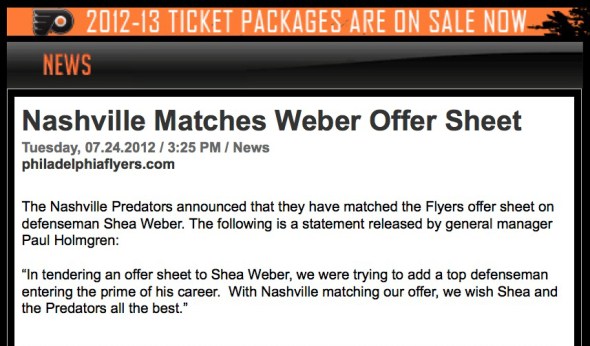

Anyone can see why Howson was so excited to complete this trade. The Columbus coup, however, was upstaged the next day by the second major news story of the week. The big headline was featured prominently on the Philadelphia Flyers’ website Tuesday:

Here’s a closer look:

Philadelphia’s four-sentence story was dwarfed by coverage around the rest of the league. Flyers GM Paul Holmgren’s terse statement contrasted with the Predators’ press release announcing “the most important hockey transaction in franchise history.”

Nashville, a feisty team on the ice, showed some spirit from the front office, defiantly proclaiming that the Predators won’t “be pushed around by teams with ‘deep pockets.'” Hear that, Minnesota?

Despite Nashville’s well deserved pride in their triumph over the would-be poachers from Pennsylvania, troubling questions remain about the loyalty and commitment of their captain after his dalliance with another team. On Tuesday The Tennessean quoted Weber’s agent, Jarrett Bousquet, saying, “He’s glad to be back…. He’s really happy that ownership made the commitment to him.”

Five days earlier, Bousquet had told TSN Radio 1050 Toronto that Weber would “like to play with the Philadelphia Flyers. He doesn’t want to go through a rebuilding process again.”

Weber himself, slinking back into town with his Predator tail between his legs, disavowed Bousquet’s claims that he wanted to leave Nashville. According to The Tennessean, Weber said in a teleconference yesterday, “I was never a part of any of that. I didn’t make any statements publicly.”

Like a straying husband trying to win back a betrayed wife, Weber professed deep feelings for the city of Nashville, the people of Nashville, and the on-ice employees of Nashville: “I love the city of Nashville. I love the fans and my teammates.” He even expressed great affection for the Predators’ facility, saying “everyone that has played [in Nashville] knows how great the city is and … they love the atmosphere at the rink.”

But surely fans and teammates anxious for reassurance can’t help but notice that Weber failed to mention the franchise and team itself and said nothing about how great it is to play for Nashville. No doubt Nashville boasts better barbecue and warmer weather than Philly, but does Weber really want to play there?

The Predators may put on a good face, but they must confront the strong likelihood that their longtime captain and franchise player would rather not be with them. General manager David Poile, quoted on the league website, likened the 14-year contract to “a marriage”; given that Weber was dragged to the altar after attempting to elope with the Flyers, some marital counseling may be in order.

History does offer hope for reconciliation between Weber and the Predators. Avalanche captain Joe Sakic had a well publicized fling with the Rangers in 1997, signing a front-loaded $21 million offer sheet designed to break the bank for a financially struggling Colorado franchise, but the flirtation was never consummated and, over time, Avs fans renewed their love affair with Sakic. Unlike Weber, though, Sakic made sure his affection for Denver was never in doubt, reported in the (New York) Daily News as saying, “Everyone knows how much I like it here.”

Nashville is not alone in experiencing a captain’s betrayal. The Predators at least have a chance to mend their relationship with their captain; two other teams this summer have lost their star captains entirely. Zach Parise, fresh off a Stanley Cup Finals appearance, fled New Jersey for his home-state team and $98 million. And Nash, who requested a trade away from the Blue Jackets months ago during the season, was clearly thrilled to escape Columbus. The giddy Rangers said on their website that joining New York was a dream come true for Nash and offered a “Rick Nash Quote Book” featuring such memorable lines as: “I wanted to play somewhere that I wanted to be and my number one priority was to be here, and I’m just happy it worked out. This is a world class team, and I’m excited to be here.”

Every NHL locker room has a revolving door; players constantly come and go. But losing a captain is more than an ordinary roster change and is particularly disheartening when the captain runs for the exit. One other team lost its captain this summer to retirement, but the end of Nick Lidstrom’s tenure is also an occasion to celebrate his long, productive, and exclusive relationship with the Red Wings. The departures of Parise and Nash and the near loss of Weber were rejections of their respective teams, and for New Jersey and Columbus, outright abandonment.

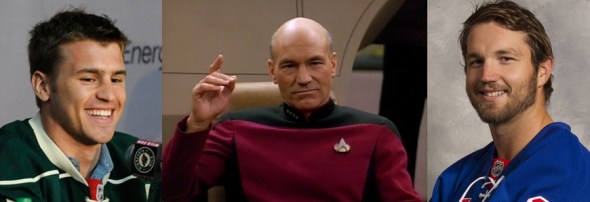

A captain isn’t supposed to abandon ship — even when it’s sinking and certainly not when it just sailed to the Cup Finals. Didn’t Rick Nash or Zach Parise ever watch Star Trek? Captain Picard, the epitome of leadership on the final frontier, always resorted to self-destructing the ship before he’d surrender the Enterprise.

In space, at sea, or on the ice, being abandoned by a captain is tough to take. The crew members left behind can’t waste time trying to make sense of their leader’s desertion; they’ve got to scramble for the life boats or try to swim to shore. Even if they make it, they’ll probably spend some time feeling marooned.

Reading the Play: Who Owns Hockey?

Posted: January 25, 2013 | Author: Covering the Puck | Filed under: Reading the Play (Commentary) | Comments Off on Reading the Play: Who Owns Hockey?January 25, 2013

For the NHL, this is a watershed moment: “The National Hockey League’s Board of Governors today ratified the terms of the Collective Bargaining Agreement negotiated with the NHL Players’ Association, … signaling a new era of cooperation and partnership.” After the ordeal of a rancorous labor dispute and lengthy lockout, the league is to embark on a new age of peace and prosperity.

But it’s July 22, 2005, when the NHL proclaims a new dawn, and the “new era” will not last. Seven years later, the league again locked out the players and commenced another rancorous labor dispute.

Like the fabled Aztec empire, the golden age of the National Hockey League was glorious but short-lived … although it did not end with the execution of its leader. Before its demise, the league’s new era flourished, achieving extravagant riches — more than $3 billion a year in revenue — and rapid growth — a 51% increase in franchise value.

What went wrong?

Somehow, the historic “cooperation and partnership” established between the league owners and the players in 2005 dissolved into accusations and acrimony. Who was at fault?

The dispute between league ownership and players is often dismissed as a battle of “the rich” (players) “versus the richer” (owners). The combatants are exceptionally wealthy, the fight over division of dollars is petty, and the whole mess boils down to greed.

But the relevant distinction between owners and players is not net worth; it is the position each occupies in the business of hockey. The conflict between ownership and players is better understood as employer versus employee; capital versus labor. The NHL is no different from Walmart in its agenda to minimize employee compensation and rights while exploiting employees’ talent and sweat for its own profit.

In many ways, as usual, capital has the upper hand in this fight. But the unique economics of professional sports changes the dynamics of this particular labor dispute. Ownership must confront the fundamental truth that owners are easily replaceable — with several aspiring owners waiting in the wings — but the players are not.

Predictably, NHL ownership does its best to deny this reality and portray the players as overpaid and selfish. But the common characterization of major-league professional athletes as “greedy” and “spoiled,” aided by the general public’s resentment of their large salaries, conflicts with the economic facts of the industry.

To begin with, player salaries are substantially smaller than commonly assumed. While the highest-paid superstars make headlines with their contracts, most players make far less. The number typically quoted as the average player salary in the NHL is the mean salary, $2.4 million in 2011-2012. But this figure is inflated by outliers at the top: the four players, out of about 700 players across the league, who earned $10 million or more.

A better measure of the typical player’s situation is the median salary, the midpoint between highest and lowest, which is only $1.5 million1. The mode, the salary earned by the largest group of players, is even lower: under a million at $900,0002.

One year earlier, in the 2010-2011 season, NHL executives whose salaries were reported by the league were paid an average (mean) salary of $2.2 million. The median executive salary that year was $1.5 million. (The sample was too small to have a useful mode.)

Although the two data sets are not quite comparable — the figures for player salaries are more recent and therefore inflated — they are sufficient to illustrate the relative scale of pay in the NHL.

NHL executives make the same amount of money, on average, as the players whose salaries the league insists on cutting. Commissioner Gary Bettman was paid $7.98 million; he received a larger salary in 2011 than 98% of the players did in 2012.

Of course, while NHL player salaries are nearly identical to NHL executive salaries, they are undeniably far larger than average in the economy as a whole. However, players’ unusually large salaries are consistent with the unusually large amount of revenue generated by their labor.

Major league sports is a huge business that produces billions of dollars of revenue annually from the work of a small labor force. Averaged across the four major sports leagues in North America and based on figures reported by the Chicago Tribune in November 2012, the business of professional sports generates $5.9 billion a year in revenue for each league while employing 866 players3. That’s an average of $6.8 million in revenue per player.

In comparison, the average S&P 500 company last year earned $420,000 in revenue per employee.

High player salaries are fully consistent with the revenue they produce; in this case, compensation correlates with productivity. The value of a commodity should also correlate with its scarcity — and a hockey player who makes it to the NHL is a precious rarity.

How scarce is NHL-caliber ability?

In 2012 the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) reported over 1.6 million registered hockey players across its 72 member federations worldwide. Nineteen of these member nations had a player in the NHL last season. Limiting the field to males registered in these 19 countries leaves a total of 1.36 million hockey players who might dream of playing for the Stanley Cup. The 690 players who made it to an NHL team represent 0.05% of this talent pool.

What about the value of an NHL franchise owner?

Ownership of a professional sports franchise requires one qualification: the ability to make money or the good fortune to inherit or marry into it. NHL owners are perfectly qualified for this position — they’ve been exceptionally successful in making piles and piles of money. Among the 30 franchises, 10 NHL owners have managed to accumulate $1 billion or more in net worth, all of them from the U.S. or Canada. They comprise 2.2% of the pool of 450 billionaires in these countries.

A billionaire is 44 times more likely to buy an NHL franchise than a male hockey player is to make an NHL team. Put another way, an NHL-caliber player is 44 times more scarce than an NHL-owning billionaire — and scarcity, if any Econ 101 textbook can be trusted, drives economic value.

As employees, NHL players are compensated not only for high productivity and a rare skill set. Their occupation requires personal sacrifices: they give up time with their families, the stability of living in the same city from one year to the next, and most of all, their own health. Players risk serious injury every time they step on the ice. Injury can entail major surgery, painful rehab, and sometimes long-term physical, psychological, and cognitive damage. Cumulative or acute injuries that shorten or end careers can also cost millions in lost income.

The NHL obscures public information about injuries, but data tracked down and compiled by The Globe and Mail reports a total of 6,751 man-games lost to injury near the end of the 2010-2011 season, with an average of nine games still remaining for each team. On average, at every NHL game, three players on each team are unable to play due to injury.

Information on the number of sick days taken by Gary Bettman and other league executives and owners that year does not appear to be readily available. The number of work-related surgeries, lost teeth, and stitches among all NHL owners and executives is estimated to be zero.

Anyone with a fat bank account can buy a hockey team, but only a special few can play for it. How much do owners contribute to producing the $3 billion in annual league revenue? How much is due solely to the talent and sacrifice of the players?

But the NHL’s repeated labor disputes are not only about economics. At a deeper level, this conflict is about the meaning and ownership of hockey.

To NHL franchises, hockey is a commodity sold for profit. The league stages games to sell tickets — the single biggest source of revenue, comprising fully half of league income — and to drive demand for ancillary products such as broadcast rights, licensed merchandise, and concessions. For NHL owners, selling the game of hockey is like making widgets.

To players, hockey is a livelihood, a trade, but also a calling. They may be human widgets in the eyes of ownership, but professional hockey players are more akin to virtuoso artists. They practice an esoteric craft at the highest level, and by performing it for the pleasure of others are able to earn a living. Most hockey players, like most painters, musicians, and writers, can pursue their art only as a hobby. Most pay for the privilege. Only the rarest practitioners succeed in turning a passion into a career.

The league owns the franchises, but it does not own the game and it does not own the players.

To the owners, their employers, the players owe only the fulfillment of their contract obligations. Loftier contributions such as loyalty, respect, or even giving a damn about their work are purely optional; ownership and management don’t always grant these courtesies to players and they are not entitled to receive them. Players care because they owe it to themselves and they owe it to the magnificent game they are privileged to play.

Hockey belongs to its players. Not the owners who sign NHL paychecks, not the rinks that rent ice time, not even the fans who buy tickets. The players alone bring the game to life. From peewee to the pros, from the shaky adult beginner to the aspiring Olympian, every hockey player understands — and lives — the spirit of the game in a way no franchise owner, business executive, or league commissioner ever can.

Hockey lovers who return to the NHL after each corrosive labor dispute are drawn by the joy of witnessing the game performed at its highest level. The players are both the creators of this product and its sole owners — and no lockout or CBA can change that.

1 Calculations based on figures from the USA Today NHL salary database.

2 Calculations based on figures from the USA Today NHL salary database.

3 Based on number of teams multiplied by roster size: NFL, NBA, MLB, NHL.