Loose Pucks: Curse of the Blue Shirts

Posted: January 29, 2013 Filed under: Loose Pucks (Miscellaneous) Comments Off on Loose Pucks: Curse of the Blue ShirtsJanuary 29, 2013

As discussed previously, new Sharks pickup Scott Gomez is attempting to reverse a steep career decline. The former star’s career has plummeted from lofty heights — taking home the Calder Trophy as rookie of the year and winning two Stanley Cups with the Devils — to stunning lows — a humiliating contract buyout in Montreal and a spot on the fourth line in San Jose.

Gomez suffered a sharp decline in production after his first year in Montreal. In 2009-2010, after the Canadiens acquired Gomez and the rest of his $51.5 million seven-year contract from the Rangers, he scored 59 points in 78 games, or 0.756 points per game. In the following two seasons, he produced only three more points while playing 40 more games, for a point-per-game average of 0.525. That’s more than a 30% drop in scoring.

No one seems able to explain the sudden and drastic loss of scoring ability, least of all Gomez himself. During the dark days of his more than year-long stretch without scoring a goal, The (Montreal) Gazette could only ask plaintively, “Will Scott Gomez ever score again?” Gomez simply expressed disbelief: “This whole thing is surreal to me now. I can’t help but think: ‘Are you kidding me?'”

But Gomez may not be directly responsible for the spectacular collapse of his hockey career. Perhaps he simply succumbed to the malady that has claimed many stronger victims before him: the Rangers curse.

It was the New York Rangers who originally signed Gomez to the bloated contract that Montreal just unloaded. Before the Rangers came calling, Gomez was doing just fine in New Jersey. Then the spendthrift Rangers snapped up their Tristate neighbors’ rising star, showered him with cash, and ushered in the inevitable demise of his hockey career.

The Rangers have a history of spending freely (and conspicuously) to buy other teams’ talent. Why nurture home-grown talent when you can just buy players someone else nurtured for you? Like any rich New Yorker, the Rangers aren’t about to take the subway to success when they have plenty of cash to pay for a cab.

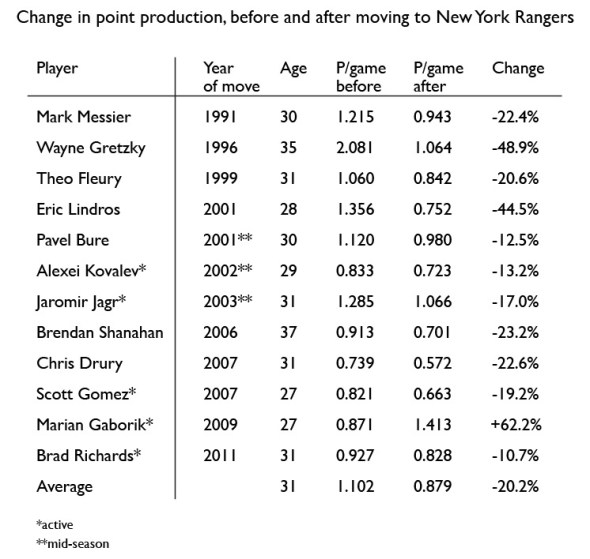

The trouble is, most of their blockbuster acquisitions broke down after a few miles. Moving to Manhattan, for NHL players, can spell doom for even the most promising career. Consider these statistics for the following 12 high-profile Ranger acquisitions during the 1990s and 2000s:

The wrong move

Mark Messier led the Rangers to a Stanley Cup, and he still couldn’t escape the Rangers curse; his scoring dropped 22%. Wayne Gretzky is Wayne Gretzky, and he couldn’t escape it either: his points per game decreased almost by half.

Even Alexei Kovalev couldn’t escape the Rangers curse, and he started with the Rangers. But then he went to Pittsburgh for five seasons, where he recorded a career-high 95 points in 2000-2001. After enjoying success outside New York City, Kovalev was just asking for trouble when he moved back to the Rangers during the 2002-2003 season. His point production dropped by 13% from his previous average (including his original stint with the Rangers). Leaving another NHL team and moving to Madison Square Garden is how players catch the Rangers curse, and previous exposure does not provide immunity.

One player does seem to have overcome the odds and beaten the curse: Marian Gaborik has so far achieved an increase in points per game since coming to the Rangers, though he will still need to monitor the remaining years of his career for symptoms. Maybe he has a genetic anomaly that reduces his susceptibility. Even the Black Death spared a lucky few.

Overall, however, the data clearly establishes substantial loss in scoring following a move to the Rangers. Of course, other factors could contribute to the post-Rangers decline in scoring — lack of chemistry with new teammates, perhaps; difficulty coping with the pressure of a gaudy contract and heavy expectations; or simply the passage of time as players enter the later stages of their careers. To determine the true effect of the Rangers curse independent of general adjustments, normal career decline, and other secondary factors, a control group is needed. Fortunately, history provides the perfect case study, the superstar player the Rangers went after but didn’t get: Joe Sakic.

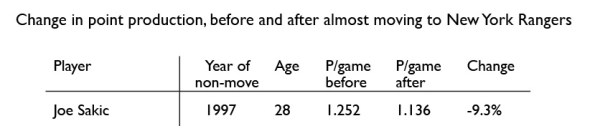

In the summer of 1997 the Rangers signed Sakic, then a Group 2 free agent, to an offer sheet. Had the Avalanche not matched the offer, Sakic would have begun his Rangers career the following season. Here are his numbers:

Dodged a bullet

Like the sufferers of the Rangers curse, Sakic produced fewer points in the second segment of his career — that is, during the seasons following his near-move to the Rangers. But Sakic’s scoring decreased by only 9.3%, while scoring by the players who actually did move to the Rangers dropped by 20.2%, more than twice as much. Sakic was younger at the time of his non-move than the Rangers group as a whole when they did move, but Eric Lindros is the only Ranger of comparable age whose career, like Sakic’s, has already ended — and Lindros suffered a particularly severe case of the curse with an appalling 44.5% drop in scoring.

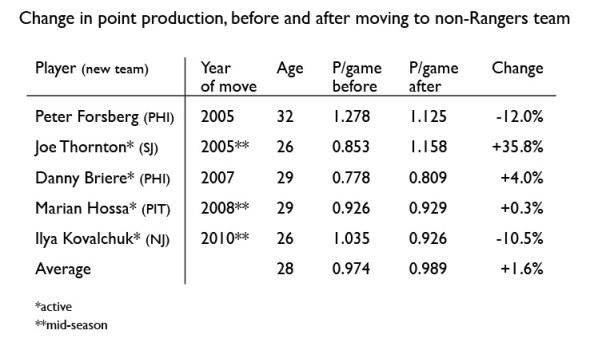

Sakic’s unique status as an almost-Ranger provides a helpful comparison, but he’s still only one player — too small a sample size to be convincing alone. For a second control group, consider the following six high-profile acquisitions by teams other than the Rangers:

Good hygiene

On average, prominent players who moved to teams other than the Rangers actually increased their scoring slightly after the move. The difference between the non-Ranger group’s 1.6% increase in scoring and the Ranger group’s 20.2% decrease is almost 22 percentage points.

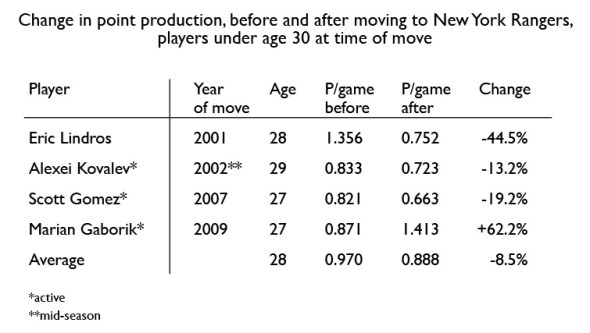

In fairness, these players were three years younger than the Rangers group, as a whole, when they changed teams. (Age at the time of the move is based on opening day of the new season for offseason acquisitions or the date of the trade for mid-season acquisitions.) Just to be sure, look at the Rangers group again, this time limiting it to players under age 30 when they moved:

Young and robust … but not immune

These younger players changed teams at the same age as the control group (28 on average), but their scoring still decreased 8.5% compared to the control group’s 1.6% increase — a 10-percentage-point difference. While this particular comparison is useful for addressing the age factor, it’s important to note that most players in this age group — both Rangers and non-Rangers — are still active in the NHL, so their final career trajectories are yet to be determined.

Taken in totality, however, empirical analysis of the available data leads to only one conclusion.

Yes, the Rangers curse is real. But how bad is it really?

To put the numbers in perspective, it’s helpful to see what a small percentage-point difference can mean in terms of real-life changes. Conveniently, the real world offers a useful model in the stock market, which like a hockey player’s scoring is measured in points.

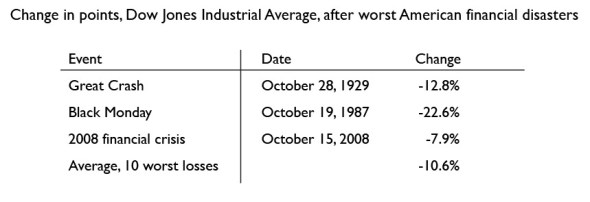

Based on data from The Wall Street Journal, here are three of the worst one-day losses in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, as well as an average of the 10 worst losses all time, in U.S. history:

Free fall

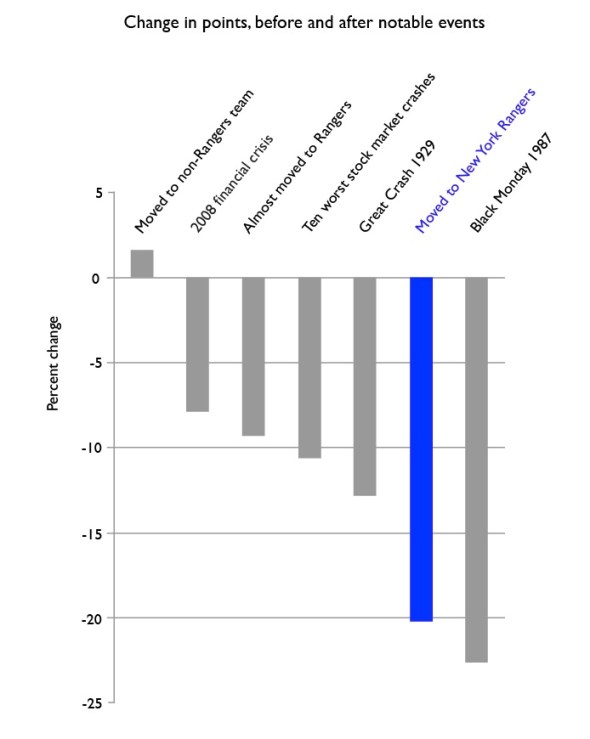

Put it all together and a clear picture emerges, revealing a virulent sickness in the NHL. For the visually oriented, here is the data aggregated in a graph showing the percentage change in points before and after several notable events, including a move to the New York Rangers:

Worst calamities

Distilled into simple terms, the Rangers curse is more destructive than the stock market crash preceding the Great Depression. But the effects of the curse are slightly better than the single worst nosedive in American financial history, Black Monday in 1987. Perhaps new additions to the Rangers can find a measure of comfort in that fact.

Can a cure be found? Funding for research has yet to present itself, despite all of the disease’s victims being celebrities. The prospects for treatment seem dim.

Rick Nash, take your vitamins.

You must be logged in to post a comment.